The stagnation of wages in the United States since the early 1970s is a complex and multifaceted issue that can be attributed to a combination of historical events, economic policies, and societal changes.

Let’s explore the various dimensions that have contributed to this prolonged wage stagnation and delve into the significant impact of inflation triggered by the Nixon administration’s decision to abandon the gold standard in 1971.

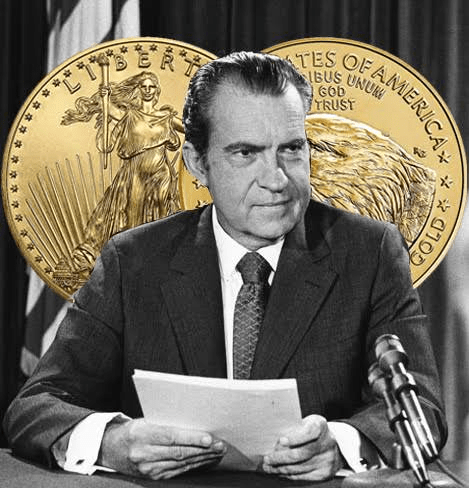

The End of the Gold Standard (1971): President Richard Nixon’s move to end the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold marked a pivotal moment in economic history. This decision transformed the U.S. dollar from a currency backed by a tangible asset into a fiat currency, not directly tied to any physical commodity. While this transition allowed the government to exercise more control over its monetary policy, it also opened the door to increased money supply through mechanisms like quantitative easing. Consequently, this led to inflationary pressures, as more dollars were being introduced into the economy without a corresponding increase in tangible assets.

The impact of this inflationary environment was far-reaching and had a profound effect on wage growth. Inflation eroded the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar over time. As the cost of living rose due to inflation, workers found that their wages could buy less in terms of goods and services. This effectively translated into stagnant or even declining real wages, as nominal wage increases failed to keep pace with the rising cost of living.

The Oil Crisis (1973 and 1979): Another crucial factor contributing to wage stagnation in the 1970s was the oil crises of 1973 and 1979. These crises, caused by OPEC’s oil embargoes, had a two-fold impact on the U.S. economy. First, they led to skyrocketing energy prices, which inflated production costs across various industries. This, in turn, reduced profit margins for businesses and limited their ability to increase employee wages.

Second, the oil crises triggered broader economic disruptions, including economic stagnation and recessionary periods. These adverse economic conditions made it challenging for businesses to invest in wage growth, as they were focused on managing the economic fallout and maintaining financial stability.

Obesity and Dietary Shifts: The late 1970s saw the U.S. government advocating for low-fat diets, indirectly influencing dietary habits across the nation. The shift towards higher carbohydrate consumption is associated with rising obesity rates, which had several economic consequences. Health issues related to obesity, such as increased healthcare costs and reduced workforce productivity, not only strained individuals but also put pressure on employers. These additional financial burdens likely limited their ability to allocate resources for wage increases.

Income Inequality and Other Factors: Wage stagnation was further exacerbated by broader societal changes, including a growing income inequality gap, declining union membership, shifts in education policies, and tax reforms that disproportionately favored the wealthy. These factors collectively created an environment where wage growth was concentrated among the highest earners, leaving a large portion of the workforce with stagnant incomes.

Prognosis

The stagnation of wages in the United States since the early 1970s is a multifaceted issue influenced by a convergence of economic, policy, and societal factors.

The pivotal decision to end the gold standard in 1971 set the stage for inflationary pressures, eroding the real value of wages over time.

Combined with the oil crises, dietary shifts, and broader socio-economic changes, these factors have contributed to the persistence of wage stagnation, with the majority of American workers experiencing limited real wage growth for several decades.

Addressing this issue requires a comprehensive approach that considers both monetary policy and a range of economic and societal factors to promote equitable and sustainable wage growth for all workers.