Plagiarism has stirred discussions in various online circles, captivating attention in both the Philippines and the United States.

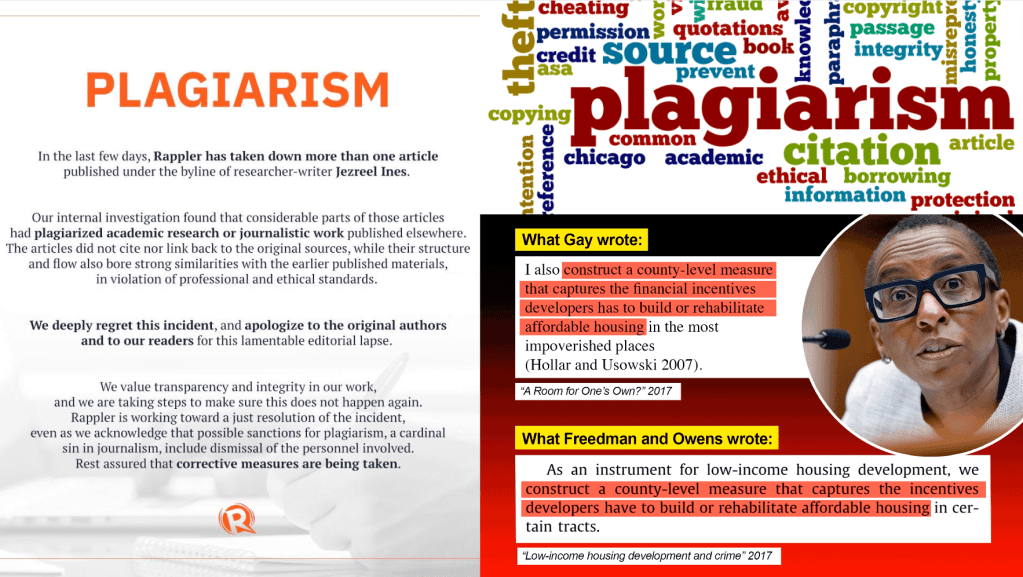

Before digital newspaper Rappler publicly admitted to a “lamentable editorial lapse,” confessing to a staff member’s guilt in copy-pasting, netizens, particularly in the United States, were engrossed in condemning Claudine Gay, the former Harvard president.

Gay resigned amid controversy surrounding “antisemitic” remarks during a congressional hearing and accusations of plagiarism.

While plagiarism remains a cardinal sin in journalism and academia, there exists a disparity in how Filipinos and Americans handle such transgressions.

In Gay’s case, despite her resignation and continued role as a tenured faculty member earning $900,000 annually, America’s leftist or liberal media seemingly attributes blame to “conservatives” for allegedly “weaponizing” plagiarism to “trap” Gay.

According to the liberal media, controlling global culture, Gay is portrayed as a victim, and “conservatives” are depicted as bullies attempting to force out “the first Black woman to serve as Harvard’s president and a political scientist held in high regard by her peers,” as put forth by liberal Politico.

Conversely, in the Philippines, the widely publicized case of Rappler researcher-writer Jezreel Ines, though largely overlooked by the mainstream media, unfolded differently.

Observers speculate Rappler’s actions were to save face, responding to calls by an academic and medical researcher from Hawaii, alleging Ines plagiarized their research paper.

Some netizens feel Ines, a UP Diliman journalism alumnus, was unjustly thrown under the bus.

However, questions arise about the role of the digital paper’s copy editor. Every campus journalist understands the responsibility of the copy editor, or the editorial staff, to thoroughly fact-check before publishing.

In Ines’s deleted story, many statements or phrases seem inspired by research that should have undergone intensive fact-checking.

Hence, had Rappler’s copy editor performed their job diligently, they could have prevented plagiarism from slipping through the cracks, avoiding this unnecessary copy-paste issue.

Now, we have recently learned that Rappler has completely removed Ines from its staff list and archives. Whether he resigned or was terminated, our empathy extends to him. Additionally, the UP alumnus has also restricted access to his X account.

Fortunately, the political landscape in the Philippines doesn’t adhere to the ‘Liberals versus Conservatives’ brand of partisan politics. Had it been the case, Mr. Ines’s plagiarism story might have taken a different turn, possibly in his favor, especially considering Maria Ressa, Rappler’s boss, identifies with the American liberal/democratic ideology.

Nevertheless, the seriousness of plagiarism takes center stage when involving government officials and private organizations engaged with the government.

This is exemplified by government contractor DDB Philippines, facing the abrupt termination of its $900,000 contract with the Department of Tourism over allegations of using “plagiarized” stock footage instead of creating original content.

Prominent Filipino figures, including former senator Tito Sotto and business leader Manny V. Pangilinan, also faced allegations of plagiarism.

Pangilinan voluntarily resigned as chair of Ateneo de Manila University’s board of trustees due to accusations regarding commencement exercise speeches in 2010. Sotto, refusing to apologize, attributed copy-pasting without attribution to an unnamed speechwriter, sparking a debate over the severity of plagiarism versus ghost-writing.

The examples presented highlight a common motivation behind plagiarism— laziness and dishonesty.

In the Philippines, a lack of updated research on plagiarism in the academe and its treatment is evident.

In 2019, a research initiative scrutinized 25 instances of plagiarism identified within scientific publications involving both faculty members and students from the University of the Philippines.

Titled ‘Internal Affairs: The Fate of Authors from the University of the Philippines Accused of Plagiarism, 1990s to 2010s,’ the research revealed what appears to be a lack of seriousness in addressing plagiarism within UP.

“[A]s our data shows, the absence of clear guidelines has left responses to plagiarism—from harsh penalties to no punishment at all—entirely within the discretion of UP publishers,” the research reads.

The researchers also found that plagiarism accusations, or having been found guilty of it, do not necessarily lead to a loss of credibility.

“One possible explanation is that most of those charged and proven to have committed plagiarism in these cases may have been able to rely on the mitigating circumstance of being a first-time/one-time offender,” the study states.

We agree with the study’s truism that, “Without plagiarism checks, a scholarly publisher risks publishing texts that not only fail to follow accepted norms of attribution, but also potentially pollute or distort scientific literature, making the previously published (perhaps even refuted or falsified) seem novel, or obscuring the actual progression of scholarly inquiry on a particular matter.”

To test this assertion, we undertook a straightforward investigation using online sources and tools, uncovering potential plagiarism by a seemingly proud academic researcher and state college professor.

We then reported the matter to the publication that published the professor’s work in 2018, which appears riddled with instances of copied information and phrases from various scholarly sources. As of this post, we still await a response from the editorial staff of this scholarly publication.

In the interconnected world of information, where the lines between originality and imitation blur, the tale of Jezreel Ines, Claudine Gay, and others reverberates as a cautionary symphony. The challenges posed by plagiarism prompt us to ponder not only the immediate consequences for the accused but also the enduring impact on intellectual integrity.